WRMD∙Surveillance: Enhanced Wildlife Disease Surveillance Application

A novel wildlife disease surveillance tool for improving our understanding of wildlife health threats in California

We wanted to reach out to say a special thank you to our network of partnering centers for their willingness to collaborate with us on the Enhanced Wildlife Disease Surveillance project! Now that the WRMD∙Surveillance application has been active for a few months, we wanted to start reaching out to centers with regular communications. Through these communications, we aim to keep you informed of the information we are learning about wildlife health patterns in California; update you on interesting findings resulting from additional diagnostic testing conducted by California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) in response to the alerts and in collaboration with participating centers; and also hear from you regarding any unusual patterns you have observed in your admissions or information you would like to relay about the health of your patients as well as questions you have about the project.

Positive Impacts of the Application

Traditionally, wildlife disease surveillance systems have been specific to a particular disease. As such, these systems can miss trends that may signify a previously unknown disease or threat to wildlife health. This application allows for evaluation of diseases for which the cause is known (e.g., lead poisoning) and syndromes or diseases for which the cause is unknown (e.g., neurologic disease) in order to detect adverse health events that may warrant further investigation. It also facilitates early detection of wildlife disease events, enabling more timely investigations. We have included more details on the features of the application in an appendix at the end of this communication in case you are interested in learning more about how it works.Since launching the application four months ago, WRMD∙Surveillance has alerted investigators at CDFW and the Wildlife Health Center to a number of specific disease outbreaks in which the cause was known and reported by the centers, including lead poisoning in turkey vultures and trichomoniasis in doves and pigeons. This information is extremely valuable for monitoring disease trends over time. It has also alerted investigators to increased numbers of individuals presenting with the same clinical signs/syndromes suggesting a disease outbreak in which the cause of the illness was not known. For a number of these alerts, CDFW followed up with centers for further investigation. In these cases, centers often shipped fresh or frozen carcasses to CDFW for post-mortem examination and laboratory diagnostics.

Highlights of New Findings

In August, the WRMD∙Surveillance application alerted us to an adverse health event in Cooper’s hawks. Juveniles were presenting in high numbers to wildlife rehabilitation centers in poor body condition with weakness (many were unable to stand) and mental dullness. Several of the birds also presented with traumatic injuries. Post-mortem examinations performed by CDFW revealed the cause of death to be West Nile Virus (WNV). West Nile has been reported to infect more than one hundred species of birds, with jays and crows seeming to be especially susceptible to infection. Since 2002, West Nile virus has been an important cause of mortality among raptors across the United States. The clinical manifestation of infection typically presents in three phases. Phase 1 is characterized by depression, decreased food intake, and weight loss. In addition to clinical signs in phase 1, birds in phase 2 present with head tremors, green urates, mental dullness/central blindness, and weakness. Phase 3 is characterized by more severe tremors and seizures. More information about the clinical signs in raptors and caring for infected birds can be found here: https://www.raptor.umn.edu/our-research/west-nile/caring-infected-birds. According to the California Department of Public Health, there were greater numbers of reported WNV mortalities in Cooper’s hawks this year relative to previous years. The epidemiology of the virus is complex and the reason for increased numbers of affected Cooper’s hawks this year is unknown. High temperatures and drought are known to affect WNV transmission. Drought reduces water availability for birds and mosquitoes, which subsequently crowd around scant water sources, leading to higher rates of spread of the virus among populations.Earlier this fall, the application alerted us to an outbreak of neurologic disease in Eurasian collared doves in central California. Poisoning was suspected as the cause of the outbreak. CDFW followed up with centers receiving cases and the centers submitted carcasses for post-mortem examination and follow-up diagnostic testing. Results of the testing indicated that the doves were infected with Pigeon Paramyxovirus Type-1 (PPMV-1). PPMV-1 affects pigeons and doves causing depression, anorexia, excessive drinking, and diarrhea followed by neurological signs (incoordination, paralysis of wings and legs and twisting of the neck muscles) and rapid death, usually 1-3 days after the onset of clinical signs. It has been reported to cause die-offs of native and non-native species of free-flying doves in the U.S. Outside of the U.S., some strains of PPMV-1 have infected other taxa of birds, including chickens. Until recently, this virus hadn’t been detected in wild doves in California. CDFW has been investigating cases and documenting the distribution of detected infections. Detection of this PPMV-1 outbreak in Central California indicates this virus may be spreading northward by the non-native doves. The virus is spread by direct contact between birds, which is facilitated by bird feeders and bird baths. There are concerns that it could infect our native Band-tailed Pigeons and Mourning Doves. We are interested in continued monitoring of infection of native and non-native doves and pigeons and potential impacts on native species in California.Currently, alerts in the application indicate an adverse health event in Western and Clark’s Grebes. Several grebes are presenting to centers in central and southern California with emaciation. CDFW is also receiving reports of ill and dying grebes at the Salton Sea and is working with centers and field biologists to conduct post-mortem examinations and laboratory analyses to investigate the cause(s). These alerts mirror findings by scientists documenting a downward trend in these populations along the Pacific Coast, which is hypothesized to be due in part to a change in the abundance and availability of their food base. We will provide results of this and other investigations in upcoming communications.

Gratitude for Partnership

Now, more than ever, there is a critical need for increased monitoring of threats to wildlife species, especially species that are difficult to monitor in the wild. In addition to the many positive contributions that centers bring to wildlife health and communities, the information that our partnering centers contribute to through this project is hugely beneficial for improving our understanding of threats to a diverse range of wildlife species across the state! We are so very thankful for the partnership!

Many thanks!

Terra Kelly, Wildlife Health Center, University of California Devin Dombrowski and Anthony Riberi, Wild Neighbors Database Project Nicole Carrion, Wildlife Investigations Laboratory, California Department of Fish and Wildlife Krysta Rogers, Wildlife Investigations Laboratory, California Department of Fish and WildlifePlease feel free to contact the Wildlife Investigations Laboratory at (916-358-2790) if you would like to report information and/or have questions about the investigations. Please also free to contact Terra Kelly at trkelly@ucdavis.edu or (530) 574-5093 or Devin Dombrowski at devin.dombrowski@wildneighborsdp.org if you have questions about the application and/or project.

Appendix:

Features of the WRMD∙Surveillance Application

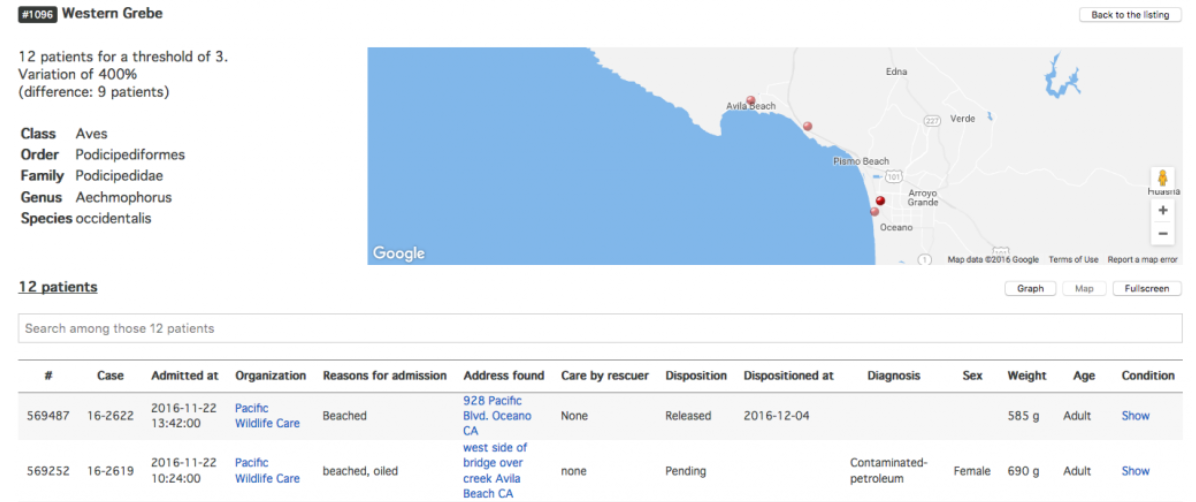

Figure 2. Map displaying the locations where the patients making up one of the alerts were found. The table at the bottom displays the supporting information for the patients making up the alert. This data improves our understanding of the reasons for admission and whether additional diagnostics would improve our understanding of the illness/event leading to the alert.

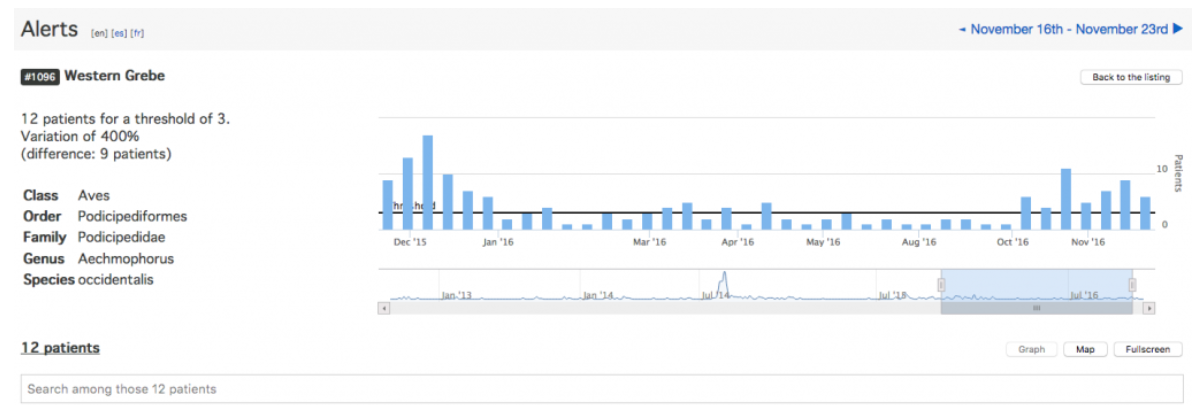

The WRMD∙Surveillance application is the first of its kind, to facilitate real-time monitoring of diseases and mortality events in California wildlife. The application aggregates data from our center network on a weekly basis and alerts investigators to potential unusual wildlife health events (e.g., disease outbreaks) based on detection of a higher than usual number of admissions of a particular species. Personally identifiable data and information related to treatment/management of cases is not accessible in the application to ensure privacy.The detailed view for each species exceeding the threshold includes a chart showing one or more years of data allowing for visualization of trends over time (Fig. 1). By using Google Maps' API, the application includes a feature in which the location found for each case is displayed on the map (Fig. 2). The mapping feature is interactive in which the investigator can click on the location depicted on the map to display the underlying data for that individual animal. The application also includes a table displaying information for patients making up the alerts (address found, disposition, diagnosis, reason for admission, sex, weight, age group, initial exam) (Fig. 2).